William Rowan Hamilton

| William Hamilton | |

|---|---|

William Rowan Hamilton (1805–1865)

|

|

| Born | 4 August 1805 Dublin |

| Died | 2 September 1865 (aged 60) Dublin |

| Fields | Physicist, astronomer, and mathematician |

| Institutions | Trinity College, Dublin |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Dublin |

| Academic advisors | John Brinkley |

| Known for | Hamilton's principle Hamiltonian mechanics Hamiltonians Hamilton–Jacobi equation Quaternions Biquaternions Hamiltonian path Icosian Calculus Nabla symbol Versor Coining the word 'tensor' Hamiltonian vector field Icosian game Universal algebra Hodograph Hamiltonian group Cayley–Hamilton theorem |

| Influences | John T. Graves |

| Influenced | Zerah Colburn Peter Guthrie Tait |

Sir William Rowan Hamilton (4 August 1805 – 2 September 1865) was an Irish physicist, astronomer, and mathematician, who made important contributions to classical mechanics, optics, and algebra. His studies of mechanical and optical systems led him to discover new mathematical concepts and techniques. His greatest contribution is perhaps the reformulation of Newtonian mechanics, now called Hamiltonian mechanics. This work has proven central to the modern study of classical field theories such as electromagnetism, and to the development of quantum mechanics. In mathematics, he is perhaps best known as the inventor of quaternions. Hamilton is said to have shown immense talent at a very early age, prompting astronomer Bishop Dr. John Brinkley to remark in 1823 of Hamilton at the age of eighteen: “This young man, I do not say will be, but is, the first mathematician of his age.”

Contents |

Life

William Rowan Hamilton's scientific career included the study of geometrical optics, classical mechanics, adaptation of dynamic methods in optical systems, applying quaternion and vector methods to problems in mechanics and in geometry, development of theories of conjugate algebraic couple functions (in which complex numbers are constructed as ordered pairs of real numbers), solvability of polynomial equations and general quintic polynomial solvable by radicals, the analysis on Fluctuating Functions (and the ideas from Fourier analysis), linear operators on quaternions and proving a result for linear operators on the space of quaternions (which is a special case of the general theorem which today is known as the Cayley–Hamilton Theorem). Hamilton also invented "Icosian Calculus", which he used to investigate closed edge paths on a dodecahedron that visit each vertex exactly once.

Early life

Hamilton was the fourth of nine children born to Sarah Hutton (1780–1817) and Archibald Hamilton (1778–1819), who lived in Dublin at 38 Dominick Street. Hamilton's father, who was from Dunboyne, worked as a solicitor. By the age of three, Hamilton had been sent to live with his uncle James Hamilton, a graduate of Trinity College who ran a school in Talbots Castle.[1] His uncle soon discovered that Hamilton had a remarkable ability to learn languages. At a young age, Hamilton displayed an uncanny ability to acquire languages (although this is disputed by some historians, who claim he had only a very basic understanding of them). At the age of seven he had already made very considerable progress in Hebrew, and before he was thirteen he had acquired, under the care of his uncle (a linguist), almost as many languages as he had years of age. These included the classical and modern European languages, as well as Persian, Arabic, Hindustani, Sanskrit, and even Marathi and Malay. He retained much of his knowledge of languages to the end of his life, often reading Persian and Arabic in his spare time, although he had long stopped studying languages, and used them just for relaxation.

At the age of 12, Hamilton met and competed with Zerah Colburn in mental arithmetic, whilst Colburn was in Dublin displaying his talents. Colburn more often than not came away the victor, which impressed Hamilton who was not used to being beaten in any contest of intellect.[2][3] Hamilton was part of a small but well-regarded school of mathematicians associated with Trinity College, Dublin, which he entered at age 18 and where he spent his life. He studied both classics and science, and was appointed Professor of Astronomy in 1827, prior to his graduation.[2]

Optics and mechanics

| Classical mechanics | ||||||||||

History of classical mechanics · Timeline of classical mechanics

|

||||||||||

Hamilton made important contributions to optics and to classical mechanics. His first discovery was in an early paper that he communicated in 1823 to Dr. Brinkley, who presented it under the title of "Caustics" in 1824 to the Royal Irish Academy. It was referred as usual to a committee. While their report acknowledged its novelty and value, they recommended further development and simplification before publication. Between 1825 to 1828 the paper grew to an immense size, mostly by the additional details which the committee had suggested. But it also became more intelligible, and the features of the new method were now easily to be seen. Until this period Hamilton himself seems to not have fully understood either the nature or importance of optics, as later he intended to apply his method to dynamics.

In 1827, Hamilton presented a theory of a single function, now known as Hamilton's principal function, that brings together mechanics, optics, and mathematics, and which helped to establish the wave theory of light. He proposed for it when he first predicted its existence in the third supplement to his "Systems of Rays", read in 1832. The Royal Irish Academy paper was finally entitled “Theory of Systems of Rays,” (23 April 1827) and the first part was printed in 1828 in the Transactions of the Royal Irish Academy. The more important contents of the second and third parts appeared in the three voluminous supplements (to the first part) which were published in the same Transactions, and in the two papers “On a General Method in Dynamics,” which appeared in the Philosophical Transactions in 1834 and 1835. In these papers, Hamilton developed his great principle of “Varying Action“. The most remarkable result of this work is the prediction that a single ray of light entering a biaxial crystal at a certain angle would emerge as a hollow cone of rays. This discovery is still known by its original name, "conical refraction".

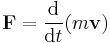

The step from optics to dynamics in the application of the method of “Varying Action” was made in 1827, and communicated to the Royal Society, in whose Philosophical Transactions for 1834 and 1835 there are two papers on the subject, which, like the “Systems of Rays,” display a mastery over symbols and a flow of mathematical language almost unequaled. The common thread running through all this work is Hamilton's principle of “Varying Action“. Although it is based on the calculus of variations and may be said to belong to the general class of problems included under the principle of least action which had been studied earlier by Pierre Louis Maupertuis, Euler, Joseph Louis Lagrange, and others, Hamilton's analysis revealed much deeper mathematical structure than had been previously understood, in particular the symmetry between momentum and position. Paradoxically, the credit for discovering the quantity now called the Lagrangian and Lagrange's equations belongs to Hamilton. Hamilton's advances enlarged greatly the class of mechanical problems that could be solved, and they represent perhaps the greatest addition which dynamics had received since the work of Isaac Newton and Lagrange. Many scientists, including Liouville, Jacobi, Darboux, Poincaré, Kolmogorov, and Arnold, have extended Hamilton's work, thereby expanding our knowledge of mechanics and differential equations.

While Hamilton's reformulation of classical mechanics is based on the same physical principles as the mechanics of Newton and Lagrange, it provides a powerful new technique for working with the equations of motion. More importantly, both the Lagrangian and Hamiltonian approaches which were initially developed to describe the motion of discrete systems, have proven critical to the study of continuous classical systems in physics, and even quantum mechanical systems. In this way, the techniques find use in electromagnetism, quantum mechanics, quantum relativity theory, and field theory.

Mathematical studies

Hamilton's mathematical studies seem to have been undertaken and carried to their full development without any assistance whatsoever, and the result is that his writings do not belong to any particular "school". Not only was Hamilton an expert as an arithmetic calculator, but he seems to have occasionally had fun in working out the result of some calculation to an enormous number of decimal places. At the age of twelve Hamilton engaged Zerah Colburn, the American "calculating boy", who was then being exhibited as a curiosity in Dublin, and did not always lose. Two years before, he had stumbled into a Latin copy of Euclid, which he eagerly devoured; and at twelve Hamilton studied Newton’s Arithmetica Universalis. This was his introduction to modern analysis. Hamilton soon began to read the Principia, and at sixteen Hamilton had mastered a great part of it, as well as some more modern works on analytical geometry and the differential calculus.

Around this time Hamilton was also preparing to enter Trinity College, Dublin, and therefore had to devote some time to classics. In mid-1822 he began a systematic study of Laplace's Mécanique Céleste.

From that time Hamilton appears to have devoted himself almost wholly to mathematics, though he always kept himself well acquainted with the progress of science both in Britain and abroad. Hamilton found an important defect in one of Laplace’s demonstrations, and he was induced by a friend to write out his remarks, so that they could be shown to Dr. John Brinkley, then the first Astronomer Royal for Ireland, and an accomplished mathematician. Brinkley seems to have immediately perceived Hamilton's talents, and to have encouraged him in the kindest way.

Hamilton’s career at College was perhaps unexampled. Amongst a number of extraordinary competitors, he was first in every subject and at every examination. He achieved the rare distinction of obtaining an optime for both Greek and for physics. Hamilton might have attained many more such honours (he was expected to win both the gold medals at the degree examination), if his career as a student had not been cut short by an unprecedented event. This was Hamilton’s appointment to the Andrews Professorship of Astronomy in the University of Dublin, vacated by Dr. Brinkley in 1827. The chair was not exactly offered to him, as has been sometimes asserted, but the electors, having met and talked over the subject, authorized Hamilton's personal friend (also an elector) to urge Hamilton to become a candidate, a step which Hamilton's modesty had prevented him from taking. Thus, when barely 22, Hamilton was established at the Dunsink Observatory, near Dublin.

Hamilton was not especially suited for the post, because although he had a profound acquaintance with theoretical astronomy, he had paid little attention to the regular work of the practical astronomer. Hamilton’s time was better employed in original investigations than it would have been spent in observations made even with the best of instruments. Hamilton was intended by the university authorities who elected him to the professorship of astronomy to spend his time as he best could for the advancement of science, without being tied down to any particular branch. If Hamilton had devoted himself to practical astronomy, the University of Dublin would assuredly have furnished him with instruments and an adequate staff of assistants.

In 1835, being secretary to the meeting of the British Association which was held that year in Dublin, he was knighted by the lord-lieutenant. Other honours rapidly succeeded, among which his election in 1837 to the president’s chair in the Royal Irish Academy, and the rare distinction of being made a corresponding member of the Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences. Later, in 1864, the newly established United States National Academy of Sciences elected its first Foreign Associates, and decided to put Hamilton's name on top of their list.[4]

Quaternions

The other great contribution Hamilton made to mathematical science was his discovery of quaternions in 1843.

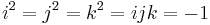

Hamilton was looking for ways of extending complex numbers (which can be viewed as points on a 2-dimensional plane) to higher spatial dimensions. He could not do so for 3 dimensions, and it was later shown that it is impossible. Eventually Hamilton tried 4 dimensions and created quaternions. According to Hamilton, on 16 October he was out walking along the Royal Canal in Dublin with his wife when the solution in the form of the equation

suddenly occurred to him; Hamilton then promptly carved this equation using his penknife into the side of the nearby Broom Bridge (which Hamilton called Brougham Bridge), for fear he would forget it. This event marks the discovery of the quaternion group. Since 1989, the National University of Ireland, Maynooth has organized a pilgrimage, where mathematicians take a walk from Dunsink Observatory to the bridge, where no trace of the carving remains, though a stone plaque does commemorate the discovery.

The quaternion involved abandoning commutativity, a radical step for the time. Not only this, but Hamilton had in a sense invented the cross and dot products of vector algebra. Hamilton also described a quaternion as an ordered four-element multiple of real numbers, and described the first element as the 'scalar' part, and the remaining three as the 'vector' part.

Hamilton introduced, as a method of analysis, both quaternions and biquaternions, the extension to eight dimensions by introduction of complex number coefficients. When his work was assembled in 1853, the book Lectures on Quaternions had "formed the subject of successive courses of lectures, delivered in 1848 and subsequent years, in the Halls of Trinity College, Dublin". Hamilton confidently declared that quaternions would be found to have a powerful influence as an instrument of research. When he died, Hamilton was working on a definitive statement of quaternion science. His son William Edwin Hamilton brought the Elements of Quaternions, a hefty volume of 762 pages, to publication in 1866. As copies ran short, a second edition was prepared by Charles Jasper Joly, when the book was split into two volumes, the first appearing 1899 and the second in 1901. The subject index and footnotes in this second edition improved the Elements accessibility.

Peter Guthrie Tait among others, advocated the use of Hamilton's quaternions. They were made a mandatory examination topic in Dublin, and for a while they were the only advanced mathematics taught in some American universities. However, controversy about the use of quaternions grew in the late 1800s. Some of Hamilton's supporters vociferously opposed the growing fields of vector algebra and vector calculus (from developers like Oliver Heaviside and Josiah Willard Gibbs), because quaternions provide superior notation. While this is undeniable for four dimensions, quaternions cannot be used with arbitrary dimensionality (though extensions like Clifford algebras can). Vector notation had largely replaced the "space-time" quaternions in science and engineering by the mid-20th century.

Today, the quaternions are in use by computer graphics, control theory, signal processing, and orbital mechanics, mainly for representing rotations/orientations. For example, it is common for spacecraft attitude-control systems to be commanded in terms of quaternions, which are also used to telemeter their current attitude. The rationale is that combining many quaternion transformations is more numerically stable than combining many matrix transformations. In pure mathematics, quaternions show up significantly as one of the four finite-dimensional normed division algebras over the real numbers, with applications throughout algebra and geometry.

Other originality

Hamilton originally matured his ideas before putting pen to paper. The discoveries, papers, and treatises previously mentioned might well have formed the whole work of a long and laborious life. But not to speak of his enormous collection of books, full to overflowing with new and original matter, which have been handed over to Trinity College, Dublin, the previous mentioned works barely form the greater portion of what Hamilton has published. Hamilton developed the variational principle, which was reformulated later by Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi. He also introduced Hamilton's puzzle which can be solved using the concept of a Hamiltonian path.

Hamilton's extraordinary investigations connected with the solution of algebraic equations of the fifth degree, and his examination of the results arrived at by N. H. Abel, G. B. Jerrard, and others in their researches on this subject, form another contribution to science. There is next Hamilton's paper on Fluctuating Functions, a subject which, since the time of Joseph Fourier, has been of immense and ever increasing value in physical applications of mathematics. There is also the extremely ingenious invention of the hodograph. Of his extensive investigations into the solutions (especially by numerical approximation) of certain classes of physical differential equations, only a few items have been published, at intervals, in the Philosophical Magazine.

Besides all this, Hamilton was a voluminous correspondent. Often a single letter of Hamilton's occupied from fifty to a hundred or more closely written pages, all devoted to the minute consideration of every feature of some particular problem; for it was one of the peculiar characteristics of Hamilton's mind never to be satisfied with a general understanding of a question; Hamilton pursued the problem until he knew it in all its details. Hamilton was ever courteous and kind in answering applications for assistance in the study of his works, even when his compliance must have cost him much time. He was excessively precise and hard to please with reference to the final polish of his own works for publication; and it was probably for this reason that he published so little compared with the extent of his investigations.

Death and afterwards

Hamilton retained his faculties unimpaired to the very last, and steadily continued the task of finishing the Elements of Quaternions which had occupied the last six years of his life. He died on September 2, 1865, following a severe attack of gout precipitated by excessive drinking and overeating.[5]

Hamilton is recognised as one of Ireland's leading scientists and, as Ireland becomes more aware of its scientific heritage, he is increasingly celebrated. The Hamilton Institute is an applied mathematics research institute at NUI Maynooth and the Royal Irish Academy holds an annual public Hamilton lecture at which Murray Gell-Mann, Frank Wilczek, Andrew Wiles, and Timothy Gowers have all spoken. The year 2005 was the 200th anniversary of Hamilton's birth and the Irish government designated that the Hamilton Year, celebrating Irish science. Trinity College Dublin marked the year by launching the Hamilton Mathematics Institute TCD.

A commemorative coin was issued by the Central Bank of Ireland in his honour.

Commemorations of Hamilton

- Hamilton's equations are a formulation of classical mechanics.

- Numerous other concepts and objects in mechanics, such as Hamilton's principle, Hamilton's principal function, and the Hamilton–Jacobi equation, are named after Hamilton.

- The Hamiltonian is the name of both a function (classical) and an operator (quantum) in physics, and, in a different sense, a term from graph theory.

- The RCSI Hamilton Society was founded in his name in 2004.

- The algebra of quaternions is usually denoted by H, or in blackboard bold by

, in honour of Hamilton.

, in honour of Hamilton.

Quotations

- "Time is said to have only one dimension, and space to have three dimensions. ... The mathematical quaternion partakes of both these elements; in technical language it may be said to be 'time plus space', or 'space plus time': and in this sense it has, or at least involves a reference to, four dimensions. And how the One of Time, of Space the Three, Might in the Chain of Symbols girdled be."—William Rowan Hamilton (Quoted in Robert Percival Graves' "Life of Sir William Rowan Hamilton" (3 vols., 1882, 1885, 1889))

- "He used to carry on, long trains of algebraic and arithmetical calculations in his mind, during which he was unconscious of the earthly necessity of eating; we used to bring in a ‘snack’ and leave it in his study, but a brief nod of recognition of the intrusion of the chop or cutlet was often the only result, and his thoughts went on soaring upwards."—William Edwin Hamilton (his elder son)

See also

- Arthur W. Conway

Notes

- ↑ Lewis, A. C. (2004). Hamilton, Sir William Rowan (1805–1865). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Sir William Rowan Hamilton", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Hamilton.html.

- ↑ Graves, Robert Perceval (1842). "Our portrait gallery – No. XXVI. Sir William R. Hamilton". Dublin University Magazine 19: 94–110. http://www.maths.tcd.ie/pub/HistMath/People/Hamilton/Gallery/Gallery.html.

- ↑ Graves (1889) Vol. III, pp. 204–206.

- ↑ Reville, William (2004-02-26). "Ireland's Greatest Mathematician". The Irish Times. http://understandingscience.ucc.ie/pages/sci_williamrowanhamilton.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-08.

References

- Hankins, Thomas L. (1980). Sir William Rowan Hamilton. The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0801822032., 474 pages—Primarily biographical but covers the math and physics Hamilton worked on in sufficient detail to give a flavor of the work.

- Graves, Robert Perceval (1882). "Life of Sir William Rowan Hamilton, Volume I". Dublin University Press. http://www.archive.org/details/lifeofsirwilliam01gravuoft.

- Graves, Robert Perceval (1885). "Life of Sir William Rowan Hamilton, Volume II". Dublin University Press. http://www.archive.org/details/lifeofsirwilliam02gravuoft.

- Graves, Robert Perceval (1889). "Life of Sir William Rowan Hamilton, Volume III". Dublin University Press. http://www.archive.org/details/lifeofsirwilliam03gravuoft.

External links

- MacTutor's Sir William Rowan Hamilton. School of Mathematics, University of St Andrews.

- Wilkins, David R., Sir William Rowan Hamilton. School of Mathematics, Trinity College, Dublin.

- Wolfram Research's William Rowan Hamilton

- Cheryl Haefner's Sir William Rowan Hamilton

- 1911 Britannica Hamilton

- Hamilton Trust

- The Hamilton year 2005 web site

- The Hamilton Mathematics Institute, TCD

- Hamilton Institute

- Hamilton biography

Publications

- Hamilton, William Rowan (Royal Astronomer Of Ireland), "Introductory Lecture on Astronomy". Dublin University Review and Quarterly Magazine Vol. I, Trinity College, January 1833.

- Hamilton, William Rowan, "Lectures on Quaternions". Royal Irish Academy, 1853.

- Hamilton (1866) Elements of Quaternions University of Dublin Press. Edited by William Edwin Hamilton, son of the deceased author.

- Hamilton (1899) Elements of Quaternions volume I, (1901) volume II. Edited by Charles Jasper Joly; published by Longmans, Green & Co..

- David R. Wilkins's collection of Hamilton's Mathematical Papers.